Art in the Making Impressionism Sponsors Preface Sir Archibald

Impressionism is a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small-scale, sparse, yet visible brush strokes, open up limerick, emphasis on accurate depiction of lite in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject field matter, unusual visual angles, and inclusion of movement every bit a crucial element of homo perception and experience. Impressionism originated with a group of Paris-based artists whose independent exhibitions brought them to prominence during the 1870s and 1880s.

The Impressionists faced harsh opposition from the conventional fine art community in France. The proper name of the style derives from the championship of a Claude Monet work, Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), which provoked the critic Louis Leroy to coin the term in a satirical review published in the Parisian paper Le Charivari. The development of Impressionism in the visual arts was soon followed by analogous styles in other media that became known as impressionist music and impressionist literature.

Overview [edit]

Radicals in their time, early on Impressionists violated the rules of academic painting. They constructed their pictures from freely brushed colours that took precedence over lines and contours, post-obit the example of painters such as Eugène Delacroix and J. M. Westward. Turner. They also painted realistic scenes of modern life, and oftentimes painted outdoors. Previously, notwithstanding lifes and portraits as well as landscapes were ordinarily painted in a studio.[ane] The Impressionists found that they could capture the momentary and transient effects of sunlight by painting outdoors or en plein air. They portrayed overall visual effects instead of details, and used curt "broken" brush strokes of mixed and pure unmixed colour—not blended smoothly or shaded, every bit was customary—to achieve an consequence of intense color vibration.

Impressionism emerged in France at the aforementioned time that a number of other painters, including the Italian artists known as the Macchiaioli, and Winslow Homer in the United states of america, were likewise exploring plein-air painting. The Impressionists, however, developed new techniques specific to the style. Encompassing what its adherents argued was a different manner of seeing, information technology is an art of immediacy and motion, of candid poses and compositions, of the play of calorie-free expressed in a vivid and varied apply of colour.

The public, at first hostile, gradually came to believe that the Impressionists had captured a fresh and original vision, even if the art critics and art establishment disapproved of the new style. By recreating the awareness in the eye that views the bailiwick, rather than delineating the details of the subject, and by creating a welter of techniques and forms, Impressionism is a precursor of various painting styles, including Neo-Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism.

Beginnings [edit]

In the middle of the 19th century—a fourth dimension of change, as Emperor Napoleon 3 rebuilt Paris and waged war—the Académie des Beaux-Arts dominated French art. The Académie was the preserver of traditional French painting standards of content and style. Historical subjects, religious themes, and portraits were valued; landscape and still life were non. The Académie preferred advisedly finished images that looked realistic when examined closely. Paintings in this style were made up of precise brush strokes carefully blended to hide the artist'south hand in the piece of work.[3] Colour was restrained and often toned down further by the application of a golden varnish.[four]

The Académie had an annual, juried art show, the Salon de Paris, and artists whose work was displayed in the show won prizes, garnered commissions, and enhanced their prestige. The standards of the juries represented the values of the Académie, represented by the works of such artists as Jean-Léon Gérôme and Alexandre Cabanel.

In the early 1860s, four immature painters—Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille—met while studying under the academic artist Charles Gleyre. They discovered that they shared an involvement in painting landscape and contemporary life rather than historical or mythological scenes. Following a practise that had become increasingly popular past mid-century, they often ventured into the countryside together to pigment in the open air,[5] but non for the purpose of making sketches to be developed into carefully finished works in the studio, as was the usual custom.[6] By painting in sunlight straight from nature, and making assuming employ of the bright synthetic pigments that had get available since the beginning of the century, they began to develop a lighter and brighter manner of painting that extended farther the Realism of Gustave Courbet and the Barbizon school. A favourite meeting place for the artists was the Café Guerbois on Avenue de Clichy in Paris, where the discussions were often led by Édouard Manet, whom the younger artists greatly admired. They were shortly joined by Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, and Armand Guillaumin.[seven]

During the 1860s, the Salon jury routinely rejected about half of the works submitted by Monet and his friends in favour of works past artists faithful to the approved fashion.[8] In 1863, the Salon jury rejected Manet's The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe) primarily because it depicted a nude woman with 2 clothed men at a picnic. While the Salon jury routinely accepted nudes in historical and emblematic paintings, they condemned Manet for placing a realistic nude in a contemporary setting.[9] The jury'due south severely worded rejection of Manet'south painting appalled his admirers, and the unusually large number of rejected works that twelvemonth perturbed many French artists.

After Emperor Napoleon Three saw the rejected works of 1863, he decreed that the public be allowed to guess the piece of work themselves, and the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Refused) was organized. While many viewers came simply to laugh, the Salon des Refusés drew attention to the beingness of a new trend in fine art and attracted more visitors than the regular Salon.[ten]

Artists' petitions requesting a new Salon des Refusés in 1867, and once again in 1872, were denied. In December 1873, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas and several other artists founded the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs ("Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers") to showroom their artworks independently.[xi] Members of the association were expected to forswear participation in the Salon.[12] The organizers invited a number of other progressive artists to bring together them in their inaugural exhibition, including the older Eugène Boudin, whose instance had first persuaded Monet to adopt plein air painting years before.[13] Another painter who greatly influenced Monet and his friends, Johan Jongkind, declined to participate, as did Édouard Manet. In total, thirty artists participated in their first exhibition, held in April 1874 at the studio of the photographer Nadar.

The critical response was mixed. Monet and Cézanne received the harshest attacks. Critic and humorist Louis Leroy wrote a scathing review in the newspaper Le Charivari in which, making wordplay with the title of Claude Monet'due south Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant), he gave the artists the name by which they became known. Derisively titling his article The Exhibition of the Impressionists, Leroy declared that Monet'south painting was at most, a sketch, and could hardly be termed a finished piece of work.

He wrote, in the form of a dialogue between viewers,

- "Impression—I was certain of it. I was but telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it ... and what liberty, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape."[fourteen]

The term Impressionist speedily gained favour with the public. It was as well accustomed by the artists themselves, even though they were a diverse group in mode and temperament, unified primarily past their spirit of independence and rebellion. They exhibited together—admitting with shifting membership—eight times between 1874 and 1886. The Impressionists' fashion, with its loose, spontaneous brushstrokes, would before long become synonymous with modern life.[4]

Monet, Sisley, Morisot, and Pissarro may be considered the "purest" Impressionists, in their consistent pursuit of an art of spontaneity, sunlight, and colour. Degas rejected much of this, as he believed in the primacy of cartoon over colour and belittled the practice of painting outdoors.[fifteen] Renoir turned abroad from Impressionism for a time during the 1880s, and never entirely regained his delivery to its ideas. Édouard Manet, although regarded by the Impressionists equally their leader,[16] never abandoned his liberal use of black every bit a colour (while Impressionists avoided its use and preferred to obtain darker colours by mixing), and never participated in the Impressionist exhibitions. He continued to submit his works to the Salon, where his painting Spanish Vocaliser had won a 2nd class medal in 1861, and he urged the others to do likewise, arguing that "the Salon is the real field of battle" where a reputation could be made.[17]

Among the artists of the core grouping (minus Bazille, who had died in the Franco-Prussian State of war in 1870), defections occurred as Cézanne, followed after by Renoir, Sisley, and Monet, abstained from the group exhibitions so they could submit their works to the Salon. Disagreements arose from problems such as Guillaumin's membership in the group, championed by Pissarro and Cézanne against opposition from Monet and Degas, who thought him unworthy.[18] Degas invited Mary Cassatt to display her work in the 1879 exhibition, just also insisted on the inclusion of Jean-François Raffaëlli, Ludovic Lepic, and other realists who did non represent Impressionist practices, causing Monet in 1880 to accuse the Impressionists of "opening doors to first-come daubers".[19] The grouping divided over invitations to Paul Signac and Georges Seurat to exhibit with them in 1886. Pissarro was the simply artist to show at all viii Impressionist exhibitions.

The individual artists achieved few financial rewards from the Impressionist exhibitions, but their art gradually won a caste of public acceptance and back up. Their dealer, Durand-Ruel, played a major part in this as he kept their work before the public and arranged shows for them in London and New York. Although Sisley died in poverty in 1899, Renoir had a great Salon success in 1879.[twenty] Monet became secure financially during the early 1880s and so did Pissarro past the early on 1890s. Past this fourth dimension the methods of Impressionist painting, in a diluted class, had become commonplace in Salon art.[21]

Impressionist techniques [edit]

Mary Cassatt, Lydia Leaning on Her Arms (in a theatre box), 1879

French painters who prepared the manner for Impressionism include the Romantic colourist Eugène Delacroix, the leader of the realists Gustave Courbet, and painters of the Barbizon school such as Théodore Rousseau. The Impressionists learned much from the work of Johan Barthold Jongkind, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Eugène Boudin, who painted from nature in a straight and spontaneous style that prefigured Impressionism, and who befriended and brash the younger artists.

A number of identifiable techniques and working habits contributed to the innovative style of the Impressionists. Although these methods had been used by previous artists—and are often conspicuous in the work of artists such as Frans Hals, Diego Velázquez, Peter Paul Rubens, John Constable, and J. M. West. Turner—the Impressionists were the starting time to use them all together, and with such consistency. These techniques include:

- Short, thick strokes of pigment quickly capture the essence of the subject, rather than its details. The paint is often applied impasto.

- Colours are applied side by side with as little mixing as possible, a technique that exploits the principle of simultaneous dissimilarity to make the colour announced more vivid to the viewer.

- Greys and dark tones are produced by mixing complementary colours. Pure impressionism avoids the utilise of black paint.

- Wet pigment is placed into moisture pigment without waiting for successive applications to dry, producing softer edges and intermingling of colour.

- Impressionist paintings do not exploit the transparency of thin pigment films (glazes), which earlier artists manipulated carefully to produce effects. The impressionist painting surface is typically opaque.

- The paint is practical to a white or light-coloured ground. Previously, painters often used night grey or strongly coloured grounds.

- The play of natural lite is emphasized. Close attending is paid to the reflection of colours from object to object. Painters often worked in the evening to produce effets de soir—the shadowy effects of evening or twilight.

- In paintings made en plein air (outdoors), shadows are boldly painted with the blue of the sky every bit it is reflected onto surfaces, giving a sense of freshness previously non represented in painting. (Blue shadows on snowfall inspired the technique.)

New technology played a role in the development of the mode. Impressionists took advantage of the mid-century introduction of premixed paints in tin tubes (resembling modernistic toothpaste tubes), which allowed artists to piece of work more than spontaneously, both outdoors and indoors.[22] Previously, painters fabricated their ain paints individually, past grinding and mixing dry paint powders with linseed oil, which were then stored in animal bladders.[23]

Many vivid constructed pigments became commercially available to artists for the first time during the 19th century. These included cobalt blueish, viridian, cadmium xanthous, and constructed ultramarine blue, all of which were in use by the 1840s, before Impressionism.[24] The Impressionists' manner of painting fabricated bold employ of these pigments, and of even newer colours such as cerulean blue,[4] which became commercially available to artists in the 1860s.[24]

The Impressionists' progress toward a brighter style of painting was gradual. During the 1860s, Monet and Renoir sometimes painted on canvases prepared with the traditional cherry-brown or grayness footing.[25] Past the 1870s, Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro ordinarily chose to paint on grounds of a lighter greyness or beige color, which functioned as a middle tone in the finished painting.[25] By the 1880s, some of the Impressionists had come up to prefer white or slightly off-white grounds, and no longer allowed the ground color a meaning office in the finished painting.[26]

Content and limerick [edit]

Prior to the Impressionists, other painters, notably such 17th-century Dutch painters as Jan Steen, had emphasized common subjects, just their methods of composition were traditional. They arranged their compositions and then that the main subject commanded the viewer's attention. J. M. West. Turner, while an creative person of the Romantic era, predictable the style of impressionism with his artwork.[27] The Impressionists relaxed the purlieus betwixt subject and background so that the effect of an Impressionist painting often resembles a snapshot, a part of a larger reality captured as if by run a risk.[28] Photography was gaining popularity, and as cameras became more than portable, photographs became more than aboveboard. Photography inspired Impressionists to represent momentary activeness, not only in the fleeting lights of a landscape, just in the day-to-solar day lives of people.[29] [30]

The development of Impressionism tin can be considered partly as a reaction by artists to the claiming presented by photography, which seemed to devalue the artist's skill in reproducing reality. Both portrait and mural paintings were accounted somewhat deficient and lacking in truth as photography "produced lifelike images much more than efficiently and reliably".[31]

In spite of this, photography actually inspired artists to pursue other means of creative expression, and rather than compete with photography to emulate reality, artists focused "on the i thing they could inevitably exercise better than the photograph—by further developing into an art form its very subjectivity in the conception of the image, the very subjectivity that photography eliminated".[31] The Impressionists sought to express their perceptions of nature, rather than create verbal representations. This immune artists to describe subjectively what they saw with their "tacit imperatives of gustatory modality and conscience".[32] Photography encouraged painters to exploit aspects of the painting medium, like color, which photography and so lacked: "The Impressionists were the first to consciously offer a subjective culling to the photo".[31]

Another major influence was Japanese ukiyo-east art prints (Japonism). The art of these prints contributed significantly to the "snapshot" angles and unconventional compositions that became characteristic of Impressionism. An example is Monet's Jardin à Sainte-Adresse, 1867, with its assuming blocks of colour and limerick on a strong diagonal slant showing the influence of Japanese prints.[34]

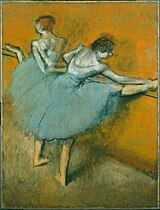

Edgar Degas was both an avid lensman and a collector of Japanese prints.[35] His The Dance Form (La classe de danse) of 1874 shows both influences in its asymmetrical composition. The dancers are seemingly caught off guard in diverse awkward poses, leaving an expanse of empty floor space in the lower right quadrant. He also captured his dancers in sculpture, such equally the Piffling Dancer of Fourteen Years.

Women Impressionists [edit]

Impressionists, in varying degrees, were looking for means to depict visual experience and contemporary subjects.[36] Women Impressionists were interested in these same ethics but had many social and career limitations compared to male Impressionists. In item, they were excluded from the imagery of the bourgeois social sphere of the boulevard, cafe, and trip the light fantastic hall.[37] As well every bit imagery, women were excluded from the formative discussions that resulted in meetings in those places; that was where male Impressionists were able to grade and share ideas near Impressionism.[37] In the academic realm, women were believed to be incapable of handling complex subjects which led teachers to restrict what they taught female students.[38] Information technology was likewise considered unladylike to excel in art since women's true talents were then believed to center on homemaking and mothering.[38]

Yet several women were able to observe success during their lifetime, fifty-fifty though their careers were afflicted past personal circumstances – Bracquemond, for example, had a husband who was resentful of her piece of work which caused her to give up painting.[39] The four virtually well known, namely, Mary Cassatt, Eva Gonzalès, Marie Bracquemond, and Berthe Morisot, are, and were, often referred to as the 'Women Impressionists'. Their participation in the series of eight Impressionist exhibitions that took place in Paris from 1874 to 1886 varied: Morisot participated in seven, Cassatt in four, Bracquemond in three, and Gonzalès did not participate.[39] [40]

The critics of the fourth dimension lumped these four together without regard to their personal styles, techniques, or subject affair.[41] Critics viewing their works at the exhibitions ofttimes attempted to acknowledge the women artists' talents but circumscribed them inside a limited notion of femininity.[42] Arguing for the suitability of Impressionist technique to women'southward fashion of perception, Parisian critic South.C. de Soissons wrote:

Ane can understand that women have no originality of thought, and that literature and music have no feminine character; but surely women know how to observe, and what they see is quite different from that which men see, and the fine art which they put in their gestures, in their toilet, in the decoration of their environment is sufficient to give is the idea of an instinctive, of a peculiar genius which resides in each one of them.[43]

While Impressionism legitimized the domestic social life as subject area matter, of which women had intimate noesis, it besides tended to limit them to that subject matter. Portrayals of frequently-identifiable sitters in domestic settings (which could offering commissions) were dominant in the exhibitions.[44] The subjects of the paintings were often women interacting with their surround past either their gaze or movement. Cassatt, in item, was aware of her placement of subjects: she kept her predominantly female person figures from objectification and cliche; when they are not reading, they antipodal, sew, drink tea, and when they are inactive, they seem lost in idea.[45]

The women Impressionists, similar their male person counterparts, were striving for "truth," for new ways of seeing and new painting techniques; each artist had an individual painting way.[46] Women Impressionists (particularly Morisot and Cassatt) were conscious of the balance of power between women and objects in their paintings – the bourgeois women depicted are non defined by decorative objects, but instead, interact with and dominate the things with which they live.[47] There are many similarities in their depictions of women who seem both at ease and subtly bars.[48] Gonzalès' Box at the Italian Opera depicts a woman staring into the distance, at ease in a social sphere but confined past the box and the man standing side by side to her. Cassatt's painting Young Girl at a Window is brighter in color but remains constrained past the canvass edge as she looks out the window.

Despite their success in their power to accept a career and Impressionism's demise attributed to its allegedly feminine characteristics (its sensuality, dependence on sensation, physicality, and fluidity) the four women artists (and other, lesser-known women Impressionists) were largely omitted from fine art historical textbooks roofing Impressionist artists until Tamar Garb's Women Impressionists published in 1986.[49] For case, Impressionism past Jean Leymarie, published in 1955 included no information on any women Impressionists.

Main Impressionists [edit]

The central figures in the development of Impressionism in France,[l] [51] listed alphabetically, were:

- Frédéric Bazille (1841–1870), who but posthumously participated in the Impressionist exhibitions

- Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894), who, younger than the others, joined forces with them in the mid-1870s

- Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), American-built-in, she lived in Paris and participated in four Impressionist exhibitions

- Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), although he later broke away from the Impressionists

- Edgar Degas (1834–1917), who despised the term Impressionist

- Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927)

- Édouard Manet (1832–1883), who did not participate in whatsoever of the Impressionist exhibitions[52]

- Claude Monet (1840–1926), the virtually prolific of the Impressionists and the one who embodies their artful almost plainly[53]

- Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) who participated in all Impressionist exhibitions except in 1879

- Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), who participated in Impressionist exhibitions in 1874, 1876, 1877 and 1882

- Alfred Sisley (1839–1899)

Gallery [edit]

Timeline: Lives of the Impressionists [edit]

The Impressionists

Associates and influenced artists [edit]

Among the close assembly of the Impressionists were several painters who adopted their methods to some degree. These include Jean-Louis Forain (who participated in Impressionist exhibitions in 1879, 1880, 1881 and 1886)[54] and Giuseppe De Nittis, an Italian artist living in Paris who participated in the first Impressionist exhibit at the invitation of Degas, although the other Impressionists disparaged his work.[55] Federico Zandomeneghi was another Italian friend of Degas who showed with the Impressionists. Eva Gonzalès was a follower of Manet who did non exhibit with the group. James Abbott McNeill Whistler was an American-born painter who played a part in Impressionism although he did not join the grouping and preferred grayed colours. Walter Sickert, an English artist, was initially a follower of Whistler, and later an important disciple of Degas; he did not exhibit with the Impressionists. In 1904 the artist and writer Wynford Dewhurst wrote the first important report of the French painters published in English, Impressionist Painting: its genesis and evolution, which did much to popularize Impressionism in Great United kingdom.

By the early 1880s, Impressionist methods were affecting, at to the lowest degree superficially, the art of the Salon. Fashionable painters such every bit Jean Béraud and Henri Gervex plant critical and financial success by brightening their palettes while retaining the smooth cease expected of Salon art.[56] Works past these artists are sometimes casually referred to as Impressionism, despite their remoteness from Impressionist practise.

The influence of the French Impressionists lasted long afterward about of them had died. Artists like J.D. Kirszenbaum were borrowing Impressionist techniques throughout the twentieth century.

Beyond French republic [edit]

As the influence of Impressionism spread beyond France, artists, likewise numerous to listing, became identified as practitioners of the new style. Some of the more important examples are:

- The American Impressionists, including Mary Cassatt, William Merritt Chase, Frederick Carl Frieseke, Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, Lilla Cabot Perry, Theodore Robinson, Edmund Charles Tarbell, John Henry Twachtman, Catherine Wiley and J. Alden Weir.

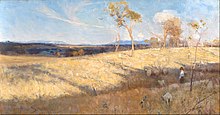

- The Australian Impressionists, including Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Walter Withers, Charles Conder and Frederick McCubbin (who were prominent members of the Heidelberg School), and John Russell, a friend of Van Gogh, Rodin, Monet and Matisse.

- The Amsterdam Impressionists in the Netherlands, including George Hendrik Breitner, Isaac Israëls, Willem Bastiaan Tholen, Willem de Zwart, Willem Witsen and Jan Toorop.

- Anna Boch, Vincent van Gogh's friend Eugène Boch, Georges Lemmen and Théo van Rysselberghe, Impressionist painters from Kingdom of belgium.

- Ivan Grohar, Rihard Jakopič, Matija Jama, and Matej Sternen, Impressionists from Slovenia. Their beginning was in the schoolhouse of Anton Ažbe in Munich and they were influenced by Jurij Šubic and Ivana Kobilca, Slovene painters working in Paris.

- Wynford Dewhurst, Walter Richard Sickert, and Philip Wilson Steer were well known Impressionist painters from the United Kingdom. Pierre Adolphe Valette, who was built-in in France simply who worked in Manchester, was the tutor of L. S. Lowry.

- The High german Impressionists, including Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, Ernst Oppler, Max Slevogt and August von Brandis.

- László Mednyánszky and Pál Szinyei-Merse in Hungary

- Theodor von Ehrmanns and Hugo Charlemont who were rare Impressionists among the more than ascendant Vienna Secessionist painters in Austria.

- William John Leech, Roderic O'Conor, and Walter Osborne in Ireland

- Konstantin Korovin and Valentin Serov in Russian federation

- Francisco Oller y Cestero, a native of Puerto Rico and a friend of Pissarro and Cézanne

- James Nairn in New Zealand

- William McTaggart in Scotland

- Laura Muntz Lyall, a Canadian creative person

- Władysław Podkowiński, a Polish Impressionist and symbolist

- Nicolae Grigorescu in Romania

- Nazmi Ziya Güran, who brought Impressionism to Turkey

- Chafik Charobim in Egypt

- Eliseu Visconti in Brazil

- Joaquín Sorolla in Spain

- Faustino Brughetti, Fernando Fader, Candido Lopez, Martín Malharro, Walter de Navazio, Ramón Silva in Argentina

- Skagen Painters a group of Scandinavian artists who painted in a small Danish fishing village

- Nadežda Petrović in Serbia

- Ásgrímur Jónsson in Republic of iceland

- Fujishima Takeji in Japan

- Frits Thaulow in Norway and later France

Sculpture, photography and film [edit]

The sculptor Auguste Rodin is sometimes called an Impressionist for the style he used roughly modeled surfaces to suggest transient lite furnishings.[57]

Pictorialist photographers whose work is characterized by soft focus and atmospheric furnishings have also been called Impressionists.

French Impressionist Cinema is a term applied to a loosely divers grouping of films and filmmakers in France from 1919 to 1929, although these years are debatable. French Impressionist filmmakers include Abel Gance, Jean Epstein, Germaine Dulac, Marcel L'Herbier, Louis Delluc, and Dmitry Kirsanoff.

Music and literature [edit]

Musical Impressionism is the proper noun given to a movement in European classical music that arose in the late 19th century and continued into the centre of the 20th century. Originating in France, musical Impressionism is characterized past suggestion and atmosphere, and eschews the emotional excesses of the Romantic era. Impressionist composers favoured short forms such equally the nocturne, arabesque, and prelude, and oft explored uncommon scales such equally the whole tone scale. Perhaps the most notable innovations of Impressionist composers were the introduction of major 7th chords and the extension of chord structures in 3rds to v- and six-part harmonies.

The influence of visual Impressionism on its musical counterpart is debatable. Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel are generally considered the greatest Impressionist composers, but Debussy disavowed the term, calling it the invention of critics. Erik Satie was also considered in this category, though his approach was regarded every bit less serious, more musical novelty in nature. Paul Dukas is another French composer sometimes considered an Impressionist, but his style is possibly more closely aligned to the late Romanticists. Musical Impressionism beyond France includes the work of such composers as Ottorino Respighi (Italy), Ralph Vaughan Williams, Cyril Scott, and John Ireland (England), Manuel De Falla and Isaac Albeniz (Spain), and Charles Griffes (America).

The term Impressionism has likewise been used to describe works of literature in which a few select details suffice to convey the sensory impressions of an incident or scene. Impressionist literature is closely related to Symbolism, with its major exemplars being Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Rimbaud, and Verlaine. Authors such as Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, Henry James, and Joseph Conrad accept written works that are Impressionistic in the way that they depict, rather than interpret, the impressions, sensations and emotions that found a graphic symbol's mental life.

Post-Impressionism [edit]

During the 1880s several artists began to develop different precepts for the use of colour, design, form, and line, derived from the Impressionist case: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. These artists were slightly younger than the Impressionists, and their work is known as mail-Impressionism. Some of the original Impressionist artists also ventured into this new territory; Camille Pissarro briefly painted in a pointillist manner, and even Monet abased strict plein air painting. Paul Cézanne, who participated in the outset and third Impressionist exhibitions, adult a highly individual vision emphasising pictorial structure, and he is more than frequently called a mail service-Impressionist. Although these cases illustrate the difficulty of assigning labels, the piece of work of the original Impressionist painters may, by definition, be categorised every bit Impressionism.

Run across also [edit]

- Fine art periods

- Cantonese school of painting

- Expressionism (as a reaction to Impressionism)

- Les XX

- Luminism (Impressionism)

Notes [edit]

- ^ Exceptions include Canaletto, who painted outside and may have used the photographic camera obscura.

- ^ Ingo F. Walther, Masterpieces of Western Fine art: A History of Art in 900 Individual Studies from the Gothic to the Nowadays Day, Part 1, Centralibros Hispania Edicion y Distribucion, S.A., 1999, ISBN 3-8228-7031-5

- ^ Nathalia Brodskaya, Impressionism, Parkstone International, 2014, pp. 13–14

- ^ a b c Samu, Margaret. "Impressionism: Art and Modernity". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 (Oct 2004)

- ^ White, Harrison C., Cynthia A. White (1993). Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting Earth. University of Chicago Printing. p. 116. ISBN 0-226-89487-eight.

- ^ Bomford et al. 1990, pp. 21–27.

- ^ Greenspan, Taube G. "Armand Guillaumin", Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Printing.

- ^ Seiberling, Grace, "Impressionism", Grove Fine art Online. Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Denvir (1990), p.133.

- ^ Denvir (1990), p.194.

- ^ Bomford et al. 1990, p. 209.

- ^ Jensen 1994, p. ninety.

- ^ Denvir (1990), p.32.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 323.

- ^ Gordon; Forge (1988), pp. xi–12.

- ^ Distel et al. (1974), p. 127.

- ^ Richardson (1976), p. 3.

- ^ Denvir (1990), p.105.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 603.

- ^ Distel, Anne, Michel Hoog, and Charles S. Moffett. 1974. Impressionism; a Centenary Exhibition, the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, Dec 12, 1974 – February ten, 1975. [New York]: [Metropolitan Museum of Art]. p. 190. ISBN 0-87099-097-7.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p. 475–476.

- ^ Bomford et al. 1990, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Renoir and the Impressionist Process Archived 2011-01-05 at the Wayback Machine. The Phillips Drove, retrieved May 21, 2011

- ^ a b Wallert, Arie; Hermens, Erma; Peek, Marja (1995). Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practise: preprints of a symposium, University of Leiden, Netherlands, 26–29 June 1995. [Marina Del Rey, Calif.]: Getty Conservation Institute. p. 159. ISBN 0-89236-322-3.

- ^ a b Stoner, Joyce Hill; Rushfield, Rebecca Anne (2012). The conservation of easel paintings. London: Routledge. p. 177. ISBN 1-136-00041-0.

- ^ Stoner, Joyce Hill; Rushfield, Rebecca Anne (2012). The conservation of easel paintings. London: Routledge. p. 178. ISBN 1-136-00041-0.

- ^ Britannica.com J.M.W. Turner

- ^ Rosenblum (1989), p. 228.

- ^ Varnedoe, J. Kirk T. The Artifice of Candor: Impressionism and Photography Reconsidered, Art in America 68, Jan 1980, pp. 66–78

- ^ Herbert, Robert 50. Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society, Yale University Press, 1988, pp. 311, 319 ISBN 0-300-05083-6

- ^ a b c Levinson, Paul (1997) The Soft Edge; a Natural History and Future of the Information Revolution, Routledge, London and New York

- ^ Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Gary Tinterow, Origins of Impressionism, Metropolitan Museum of Art,1994, page 433

- ^ Baumann; Karabelnik, et al. (1994), p. 112.

- ^ Garb, Tamar (1986). Women impressionists. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. p. ix. ISBN0-8478-0757-6. OCLC 14368525.

- ^ a b Chadwick, Whitney (2012). Women, art, and society (Fifth ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. p. 232. ISBN978-0-500-20405-iv. OCLC 792747353.

- ^ a b Garb, Tamar (1986). Women impressionists. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. p. half-dozen. ISBN0-8478-0757-6. OCLC 14368525.

- ^ a b Laurence, Madeline; Kendall, Richard (2017). "Women Artists and Impressionism". Women artists in Paris, 1850–1900. New York, New Oasis: Yale Academy Printing. p. 41. ISBN978-0-300-22393-four. OCLC 982652244.

- ^ "Berthe Morisot", National Museum of Women in the Arts. Retrieved eighteen May 2019.

- ^ Kang, Cindy (2018). Berthe Morisot: Adult female Impressionist. New York, NY: Rizzoli Electra. p. 31. ISBN978-0-8478-6131-6. OCLC 1027042476.

- ^ Garb, Tamar (1986). Women Impressionists. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. p. 36. ISBN0-8478-0757-6. OCLC 14368525.

- ^ Adler, Kathleen (1990). Perspectives on Morisot (1st ed.). New York: Hudson Hills Printing. p. 60. ISBNane-55595-049-three . Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Laurence, Madeline; Kendall, Richard (2017). "Women Artists and Impressionism". Women artists in Paris, 1850–1900. New York, New York: Yale University Printing. p. 49. ISBN978-0-300-22393-4. OCLC 982652244.

- ^ Barter, Judith A. (1998). Mary Cassatt, Modern Adult female (1st ed.). New York: Fine art Institute of Chicago in association with H.North. Abrams. pp. 63. ISBN0-8109-4089-two. OCLC 38966030.

- ^ Pfeiffer, Ingrid (2008). "Impressionism Is Feminine: On the Reception of Morisot, Cassatt, Gonzalès, and Bracquemond". Women Impressionists. Frankfurt am Master: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. p. 22. ISBN978-iii-7757-2079-iii. OCLC 183262558.

- ^ Barter, Judith A. (1998). Mary Cassatt, Mod Woman (1st ed.). New York: Fine art Constitute of Chicago in association with H.N. Abrams. pp. 65. ISBN0-8109-4089-2. OCLC 38966030.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffery (September 2008). "Longing and Constraint". Apollo. 168: 128 – via ProQuest LLC.

- ^ Adler, Kathleen (1990). Perspectives on Morisot. Edelstein, T. J., Mount Holyoke College. Art Museum. (1st ed.). New York: Hudson Hills Printing. p. 57. ISBN1-55595-049-3. OCLC 21764484.

- ^ Exposition du boulevard des Capucines (French)

- ^ Les expositions impressionnistes, Larousse (French)

- ^ Cole, Bruce (1991). Art of the Western World: From Ancient Greece to Post Modernism. Simon and Schuster. p. 242. ISBN 0-671-74728-2

- ^ Denvir (1990), p.140.

- ^ "Joconde : catalogue collectif des collections des musées de France". www.civilisation.gouv.fr . Retrieved 28 Dec 2017.

- ^ Denvir (1990), p.152.

- ^ Rewald (1973), p.476–477.

- ^ Kleiner, Fred S., and Helen Gardner (2014). Gardner's art through the ages: a concise Western history. Boston, MA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 382. ISBN 978-1-133-95479-8.

References [edit]

- Baumann, Felix Andreas, Marianne Karabelnik-Matta, Jean Sutherland Boggs, and Tobia Bezzola (1994). Degas Portraits. London: Merrell Holberton. ISBN 1-85894-014-i

- Bomford, David, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, Ashok Roy, and Raymond White (1990). Impressionism. London: National Gallery. ISBN 0-300-05035-half dozen

- Denvir, Bernard (1990). The Thames and Hudson Encyclopaedia of Impressionism. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20239-vii

- Distel, Anne, Michel Hoog, and Charles S. Moffett (1974). Impressionism; a centenary exhibition, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dec 12, 1974 – Feb 10, 1975. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-097-7

- Eisenman, Stephen F (2011). "From Corot to Monet: The Ecology of Impressionism". Milan: Skira. ISBN 88-572-0706-4.

- Gordon, Robert; Forge, Andrew (1988). Degas. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-1142-6

- Gowing, Lawrence, with Adriani, Götz; Krumrine, Mary Louise; Lewis, Mary Tompkins; Patin, Sylvie; Rewald, John (1988). Cézanne: The Early on Years 1859–1872. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Jensen, Robert (1994). Marketing modernism in fin-de-siècle Europe. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Academy Press. ISBN 0-691-03333-1.

- Moskowitz, Ira; Sérullaz, Maurice (1962). French Impressionists: A Selection of Drawings of the French 19th Century. Boston and Toronto: Trivial, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-58560-2

- Rewald, John (1973). The History of Impressionism (quaternary, Revised Ed.). New York: The Museum of Mod Fine art. ISBN 0-87070-360-9

- Richardson, John (1976). Manet (tertiary Ed.). Oxford: Phaidon Press Ltd. ISBN 0-7148-1743-0

- Rosenblum, Robert (1989). Paintings in the Musée d'Orsay. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN 1-55670-099-7

- Moffett, Charles Southward. (1986). "The New Painting, Impressionism 1874–1886". Geneva: Richard Burton SA.

External links [edit]

- Hecht Museum

- The French Impressionists (1860–1900) at Project Gutenberg

- Museumsportal Schleswig-Holstein

- Impressionism : A Centenary Exhibition, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dec 12, 1974 – February 10, 1975, fully digitized text from The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art libraries

- Suburban Pastoral The Guardian, 24 Feb 2007

- Impressionism: Paintings collected by European Museums (1999) was an art exhibition co-organized by the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, the Seattle Art Museum, and the Denver Art Museum, touring from May through December 1999. Online guided tour

- Monet's Years at Giverny: Beyond Impressionism, 1978 exhibition catalogue fully online as PDF from The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, which discusses Monet's role in this movement

- Degas: The Artist'south Mind, 1976 exhibition catalogue fully online as PDF from The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, which discusses Degas's role in this movement

- Definition of impressionism on the Tate Art Glossary

colvincleakettent.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impressionism

Post a Comment for "Art in the Making Impressionism Sponsors Preface Sir Archibald"